We Need to Tighten the International Non-Proliferation Control System

The last 50 years have seen a dangerous proliferation of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction. Since the coming into force of the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and despite its almost universal membership, at least a dozen countries have pursued clandestine nuclear weapons development. All of these clandestine programs relied heavily on the illicit acquisition of sensitive nuclear or dual-use materials, precursors, equipment and technologies in violation of well-established sanctions and export control restrictions. Such illicit acquisition and diversion were, for the most part, carried out by both state agencies and private procurement networks such as that established by Dr. A. Q. Khan. We know that various terrorist groups and a number of countries are still eyeing acquiring nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction.

The acquisition of high-technology nuclear dual-use equipment and material by illegal means has been crucial to the development of the nuclear-weapon and missile-relevant activities of North Korea and Iran. Despite extensive efforts to curtail such trafficking, both countries continued to advance their programs by such clandestine means, even after the imposition, starting in 2006, of progressively stronger UN sanctions on both states.

Given this history, there is strong reason for concern that North Korea and Iran will continue to pursue such illegal activities. The recent United States withdrawal from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and the re-imposition of broad US direct and third-party sanctions raises the strong possibility that Iran will intensify its efforts to acquire new sensitive nuclear-related equipment and technology. Close international monitoring and control will remain essential to inhibit such acquisitions. No less of concern is that other states eyeing nuclear weapon capability know, and may also seek to take advantage of, the laxness and loopholes that exist in the current control system. These factors underscore the importance of strengthening and enhancing the application and enforcement of the control mechanisms now in place.

The international community has in recent years adopted a number of international conventions, treaties, and agreements which obligate state-parties to ban the development of such weapons and to prohibit the provision of their precursors. Moreover, these have been complemented by UN Security Council resolutions, including UN Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004), condemning nuclear proliferation as a “threat to international peace and security.” The UN Security Council has also reacted to the threats posed to international peace and security by the illicit acquisition of nuclear material and dual-use items in furtherance of clandestine nuclear weapons programs in Iraq, Iran, and North Korea.

This array of international counter-nuclear proliferation agreements includes, inter alia, the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), The 1980 Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), and the 2005 International Convention on the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism. There are also a number of regional treaties that establish nuclear-weapons-free zones and multilateral arrangements that seek to limit the risks of diversion of nuclear material and dual-use items required or useful for the development of nuclear weapons.

Some members of the international community have also come together in various export control and transaction monitoring arrangements to deal with the risks of nuclear proliferation. This includes, inter alia, the 48 member Nuclear Suppliers Group, the 39 member Zangger Committee, the 27-member Global Partnership against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, the 86- member Global Initiative To Combat Nuclear Terrorism, and the 105 countries participating in the U.S. sponsored Proliferation Security Initiative. All of these arrangements engage commitments to inhibit the illicit procurement of nuclear materials and nuclear-weapons useful dual-use equipment and technology as well as other WMD related items.

These international agreements, UN Security Council resolutions and international arrangements underscore a broad international concern with the dangers posed by nuclear proliferation. They also give support to the view that nuclear proliferation activities should be considered violations of international law.

International non-proliferation obligations have also been supplemented and reinforced by UN Security Council Resolution 1540, which was adopted, in large part, to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons and materials falling into the hands of terrorists and other non-state actors. That resolution imposes an explicit and direct obligation on all countries to exercise controls not only on nuclear materials, but also over the sale, acquisition, re-export, transfer, and financing of items related to the development of nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction. This includes criminalizing illicit transactions in violation of these controls.

While Resolution 1540 is binding on all countries its provisions, like those of the international agreements, are not self-executing. They can only be given effect through the enactment, implementation, and enforcement by national authorities of national laws and regulations. There are, as of yet, no international bodies charged with export or border control, or police activities of individuals that contribute to treaty violations. Yet, the UN Security Council and other international bodies do have the ability to impose consequences on states, entities, and individuals who violate the various non-proliferation norms. These consequences can take the form of “naming and shaming,” or designating state agencies or private entities or individuals for the imposition of sanctions by all other participating or member states. The Security Council also has the authority, under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter, to authorize members to “take such action as may be necessary” to enforce these Security Council measures.

The UN Security Council’s North Korea sanctions resolutions, for example, in addition to imposing broad economic and trade sanctions, have also designated specific individuals and entities linked to the illicit procurement of banned nuclear-related material, equipment, and dual-use technology. Such designation obligates all countries to freeze their assets, block their transactions, and to ban their cross border travel. Unfortunately, the 1540 Committee has fallen short in getting many of those states in nuclear proliferation risky regions to effectively enforce such nuclear-related export control laws and border controls.

Serious gaps continue in international non-proliferation efforts, and many of the tools necessary to stem the illicit trade in nuclear-related material, equipment and technology go unused or underutilized. This includes a very uneven and inadequate application of criminal penalties on individuals and entities that engage in the illicit trade of such items. It has also proved exceedingly difficult to hold accountable those states and state agencies that directly or indirectly acquire, engage in, support, or sponsor the illicit acquisition or diversion of such items.

Strengthen the criminal salience of such illicit transactions and increasing the likelihood of effective prosecution and penalization of those involved is an essential step toward stemming such illicit activities. As a rule, such illegal transactions involve activities in multiple states. As a result, prosecutions in national courts all too often run afoul on issues related to establishing jurisdiction over the parties involved, obtaining the extradition of parties residing overseas, or challenges related to the collecting and obtaining evidence from foreign jurisdictions.

Several suggestions have been put forward to address these procedural and jurisdictional issues, including elevating transnational illicit dealings in nuclear material and dual-use items to the level of international crimes subject to universal jurisdiction. However, this category of universal jurisdiction crimes has generally been reserved for the most heinous international crimes such as crimes against humanity, torture and war crimes. Moreover, while it has also been applied to such international crimes as slave trading and piracy which often have no particular national basis, it would still represent a far reach to include illicit nuclear trade in this same category.

A similar result could still be achieved through the adoption of a new international convention supplementing the obligations now on all countries under UN Security Council Resolution 1540 to criminalize such activities. Such a convention could include, as several international conventions dealing with terrorism, drug trafficking, and international corruption have done, an obligation on states-parties to either prosecute or extradite those undertaking such illicit activities. However, this expansion of jurisdictional authority could also be accomplished more simply by broadening the application of bilateral mutual legal assistance and extradition treaties now in force.

The latest report matrix submitted by the UN’s 1540 Committee to the Security Council indicates that there has been a modest uptick in the number of countries that have enacted legislation in compliance with the 1540 resolution. Yet, few enforcement cases have yet to be reported to the committee. Moreover, the committee has been unable to document the actual scope and impact of such national control legislation.

Another 1540 Committee shortcoming is its inability to establish specific export and border control norms as a standard for implementation. Likewise, and perhaps even more importantly, it lacks the authority to adopt, maintain or publish a common list of nuclear-related material and dual-use equipment that could be commonly and uniformly controlled by all countries. While the resolution does make reference to “materials, equipment, and technology covered by relevant multilateral treaties and arrangements, or included on national control lists, which could be used for the design development production or use of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons and their means of delivery,” this same lack of specificity has, unfortunately, been reflected in many of the new control lists adopted to carry out Resolution 1540 obligations.

The critical element in the current international non-proliferation control regime is the policies and controls implemented by the principal supplier countries. This group includes the 48 members of the Nuclear Supplier Group, many of whose members are also members of the so-called Zangger Committee. The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) is a cooperative arrangement that groups together the 48 leading nuclear equipment supplier countries. Its member countries have agreed to harmonize their nuclear-related export control policies, including the implementation of an agreed “trigger list” of items to be controlled and a set of voluntary export control guidelines to be implemented as part of such controls. However, decisions on specific export applications are taken at the national level in accordance with each country’s own national export licensing laws and regulations.

The NSG guidelines contain critical licensing criteria for identifying and addressing potential risks of diversion of sensitive items. This includes assurances that the recipient state is committed and able to assure that the items are used in accordance with the licensing conditions and undertakings. There is also an undertaking by the importing country and the approved end user not to re-export or re-transfer the item to another end user, or alter the indicated end use, without first obtaining authorization from the original exporting country’s authorities. End-user checks and end-use verification procedures are also included in the guidelines and are essential elements for preventing the diversion of nuclear sensitive material and dual-use items. Replicating these measures more broadly throughout the international community would have a significant impact on reducing the risks of nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism.

Most NSG countries have assiduously implemented the agreed NSG guidelines and maintain robust export and border controls to deter violations. Nevertheless, some NSG countries have been lax when it comes to follow-up procedures, particularly concerning dual-use items. Moreover, the failure of some NSG members to carry out systematic end user and post-shipment verification procedures remains a serious proliferation-related export control lacunae.

The NSG has also been slow to adopt uniform procedures to tighten controls on the use of brokers, middlemen or other transaction intermediaries. Initially, when the NSG was founded, nearly all international nuclear trade involved direct point-to-point transactions between the manufactures and the end users. However, the broadening of international trade over the last decades has led to more complex international supply and distribution networks. Moreover, proliferators have taken advantage by setting up front companies and working through purchasing agents, brokers, and middlemen to acquire and transship the dual-use equipment destined for clandestine nuclear weapons programs. These transactions often utilized multiple intermediary destinations in countries with weaker export and border controls to serve as “turntables” for their acquisitions. They also employed complex and less than transparent payment schemes. Some experts have suggested that given the diversion risks entailed by the use of brokers and middlemen, particularly sensitive items should be subjected to direct point-point export requirements — that is “controlled delivery” from the manufacturer directly to the ultimate recipient.

The NSG guidelines also call for member countries to report and share information with other NSG members when they deny a license application for a trigger list item. Other NSG members, in turn, agree not to step in to fill the order without first consulting with the state that denied the export. However, a GAO investigation of this process revealed substantial failings and shortcomings in this regard. The GAO report also recommended that a central database on denials and known and suspected diversion networks be established upon which all NSG members could draw.

NSG member countries also have no common policy when it comes to export control enforcement measures, nor to the arrest, prosecution or penalization of export control laws and regulations. Their guidelines do not address the imposition of penalties and do not include any “prosecute or extradite” arrangements. Nor do they include specific mutual legal assistance commitments. However, The United States now insists on including such extradition clauses in its mutual legal assistance treaties.

The United States has also sponsored the international Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) which serves as a global arrangement between participating states to identify and stop the trafficking of weapons of mass destruction, their delivery systems, and related materials. PSI participants commit themselves to interdict transfers to and from states and non-state actors of proliferation concern to the extent of their capabilities and legal authorities; develop procedures to facilitate an exchange of information with other countries; strengthen national legal authorities to facilitate interdiction, and take specific actions in support of interdiction efforts. Taken in conjunction with the 2005 Protocol to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, the PSI can provide another potential platform for seeking the prosecution or extradition of nuclear proliferators.

Few, if any of the other NSG countries agree, however, with the United States’ extension of its jurisdictional reach over US licensed dual-use exports, and derivative equipment and technology wherever they are located. This includes claiming a criminal jurisdictional reach to overseas parties engaged as exporters, re-exporters, brokers, distributors, middlemen, transfer agents and end users who violate US export laws and re-export restrictions. This so-called “extraterritorial” reach of U.S. export control laws has been resisted by many of our European allies. The general approach of most NSG members, including those in the EU, once a licensed item has been lawfully exported, has been to rely on the recipient country to take responsibility for assuring adequate re-export authorization and safeguards.

Current jurisdiction limitations on the reach of national export control laws have left an open door for the establishment of international illicit procurement networks capable of eluding such controls. Such networks often consist of a string of offshore brokers, shipping agents, front companies, individuals and entities operating in countries having weak transactional oversight. They seek to mask the actual intended destination, end use or end user of the procured items and to insulate those involved from possible prosecution. The United States has tried to counter these activities by broadly applying its export control laws in such a way as to attach to the goods themselves wherever they may go. This includes goods that are produced overseas using U.S. technology as well as those originating in the United States. However, as noted above, this long arm of asserted U.S. export control jurisdiction has been strongly resisted by other countries. This makes it all the more imperative that alternative enforcement methodology be available for other nuclear equipment supplier and cooperating countries to hold those who violate its export control laws accountable.

It appears to this writer that the best road forward would be to expand the application of the international legal principle of “prosecute or extradite.” (aut dedere aut judicare). There are several ways in which this could be done. The first would be to put in place a new international agreement covering the illicit acquisition, re-transfer or smuggling of controlled nuclear material and dual-use items. The proliferation risks posed by such trade certainly merit the same degree of treatment and attention now shown to other nefarious activities as foreign political corruption or the illicit drug trade. The principle of “prosecute or extradite” is already well established with regard to those activities. Another option would be to add to the current structure of nuclear non-proliferation conventions. This could take the form of a new enforcement protocol to the NPT which already obligates states “not to provide: (a) source or special fissionable material, or (b) equipment or material especially designed or prepared for the processing, use or production of special fissionable material, to any non-nuclear-weapon State for peaceful purposes, unless the source or special fissionable material shall be subject to the safeguards required by this article.” Of course, dual-use items of nuclear proliferation concern would also have to be added to such a provision.

In any case, international crimes are, for the most part, complex and difficult to prosecute. In addition to the jurisdictional issues, there remain serious difficulties and problems in the overseas collection of evidence that is usable in courts of law. This is particularly the case with establishing criminal intent with regard to transactions involving often hard to identify controlled dual-use items. Moreover, such items can also be used for both nuclear and other non-nuclear uses. These export control cases often rely heavily on obtaining and securing evidence from various overseas countries, necessitating broad and effective judicial and international enforcement agency cooperation. Greater attention must, therefore, be afforded to the establishment of a broad series of mutual legal assistance treaties which specifically include export control violations within their scope.

The 1540 Committee has a special role to play in bringing greater attention and transparency to the implementation and enforcement of the various non-proliferation norms now in place. Strengthening their oversight mandate is key. It should include the authority to monitor and report on non-proliferation trade violations, to designate high-risk entities and individuals engaging in such transactions, and to list and specify the items that most necessary to control. The Committee also must take a more active role in assisting countries in the development and implementation of appropriate export and border control laws and measures. It is not sufficient to merely record and report the information on such laws that are provided to the committee by UN member states. Expert analysis and feedback to the reporting states are also essential.

Left unaddressed, the risks of further nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism will only intensify.

About the Author

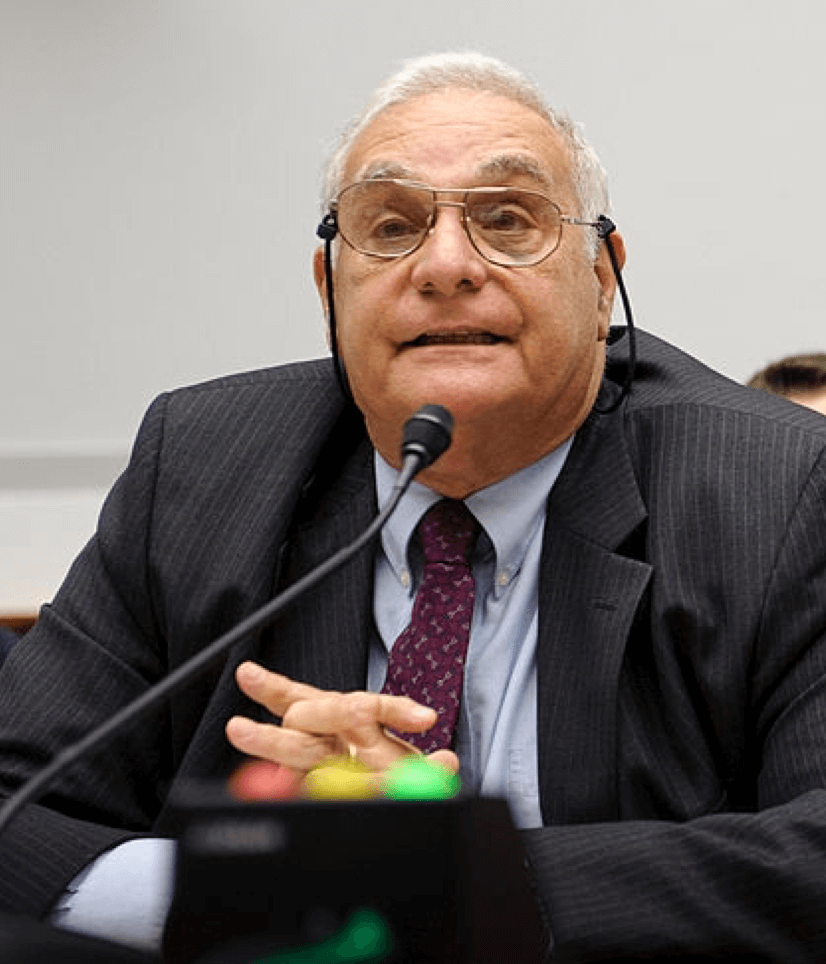

Victor Comras

BOARD MEMBER & CONTRIBUTOR

Victor Comras worked in the State Department for 35 years. In that capacity, he fulfilled a number of diplomatic functions. Among other things, Victor was the task force director for a multi-agency operation overseeing the U.S. efforts during the UN’s sanctions against Serbia in the 1990 and was also a special U.S envoy to the UN monitoring group that oversaw terrorism financing.

Related Articles

For Sake of Iranian People, Foreign Intervention Justified

As with many contemporary challenges, the case for foreign intervention in Iran has a clear precedent: NATO’s intervention in the former Yugoslavia against the regime of Slobodan Milošević.

Gaza’s Genocide Inversion: Setting the Record Straight

This video refutes the dire and growing accusation circulating globally—one that seeks to delegitimize Zionism, demonize Israel, and implicitly provoke hostility toward Jews both inside and outside the borders of the Jewish state–that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians.

The Prospects for a Democratic Transition in Venezuela

The first phase focuses on oil. Owing to sanctions, much of Venezuela’s oil production is effectively frozen. Under this plan, American companies would help rehabilitate oil production and facilitate sales, while profits would be managed in a way intended to benefit the Venezuelan population rather than fuel corruption or sustain the regime.

The Center is a gathering of scholars, experts and community stakeholders, that engage in research and dialogue in an effort to create practical policy recommendations and solutions to current local, national, and international challenges.

EXPLORE THE CENTER

FOCUS AREAS

©2025 The Palm Beach Center for Democracy and Policy Research. All Rights Reserved